I’m not one of Nature’s amassers, but a few years ago I started to collect - in a desultory sort of way - old Pan paperbacks. When I was a lad, I spent an inordinate amount of time hanging around the paperback shelves housed in the entrance to a secondhand bookshop in Wimbledon, fingering the merchandise, but without the means to buy anything (my pocket money had already been spent on sweets, I suspect).

I’m not one of Nature’s amassers, but a few years ago I started to collect - in a desultory sort of way - old Pan paperbacks. When I was a lad, I spent an inordinate amount of time hanging around the paperback shelves housed in the entrance to a secondhand bookshop in Wimbledon, fingering the merchandise, but without the means to buy anything (my pocket money had already been spent on sweets, I suspect). The cover that truly entranced me was the one for Ian Fleming’s Goldfinger. As with so many Pan covers, it promised a world of violence, mystery and glamour. (I’m still waiting, by the way.) The jacket colour - even in that dingy little doorway - positively throbbed at me. Nowadays, the pre-Connery Bond in the blue strap-line looks like a geography teacher, and the “girl” looks a bit middle-aged, but the sinister pre-Gert Frobe villain in the background still works a treat.

The cover that truly entranced me was the one for Ian Fleming’s Goldfinger. As with so many Pan covers, it promised a world of violence, mystery and glamour. (I’m still waiting, by the way.) The jacket colour - even in that dingy little doorway - positively throbbed at me. Nowadays, the pre-Connery Bond in the blue strap-line looks like a geography teacher, and the “girl” looks a bit middle-aged, but the sinister pre-Gert Frobe villain in the background still works a treat.But Pan’s covers weren’t always quite so in-your-face.

James Hilton’s classic Lost Horizon, set in the magical lamasery of Shangri-La, hidden high in the Himalayas, was the second official Pan paperback to be published in 1947. The cover features a near-abstract representation of Shangri-La. No people, no action. Perhaps they assumed it was so famous that the title alone would sell it. Then again, as they were competing with Penguin and it’s famously austere covers, they may not have wanted to appear vulgar.

James Hilton’s classic Lost Horizon, set in the magical lamasery of Shangri-La, hidden high in the Himalayas, was the second official Pan paperback to be published in 1947. The cover features a near-abstract representation of Shangri-La. No people, no action. Perhaps they assumed it was so famous that the title alone would sell it. Then again, as they were competing with Penguin and it’s famously austere covers, they may not have wanted to appear vulgar. But the advent of the post-war Mushroom publishers, with their salacious, sadistic, amoral tales of gat-toting hoodlums and trashy, curvaceous “dames” taken straight from US hard-boiled detective fiction and aimed squarely at a generation of ex-servicemen craving titillation in a grey, bombed-out, rationed Britain, changed all the rules. The publishers - one step ahead of the law and their creditors, needed to shift product fast: and that meant guys throwing punches and firing guns or impossibly nubile women wearing next to nothing.

But the advent of the post-war Mushroom publishers, with their salacious, sadistic, amoral tales of gat-toting hoodlums and trashy, curvaceous “dames” taken straight from US hard-boiled detective fiction and aimed squarely at a generation of ex-servicemen craving titillation in a grey, bombed-out, rationed Britain, changed all the rules. The publishers - one step ahead of the law and their creditors, needed to shift product fast: and that meant guys throwing punches and firing guns or impossibly nubile women wearing next to nothing.

Pan responded to the challenge, but not too abruptly. Here are two editions of Edgar Wallace’s The Ringer, published in 1951 and 1954 respectively.

Pan responded to the challenge, but not too abruptly. Here are two editions of Edgar Wallace’s The Ringer, published in 1951 and 1954 respectively.The move to realism and atmosphere - not to mention beautiful blondes - is marked. But it hasn’t yet gone the whole hog. By 1960, however, many Pan covers were practically indistinguishable from the pulp “comics” of Hank Janson’s early 1950s heyday.

But this sort of cover - which so agitated my early teenage hormones when these books, now thoroughly foxed, ended up in that Wimbledon bookshop a few years later - was already doomed: the cooler, thinner, subtler, more graphic style of the early ‘60s soon replaced it. Here are two editions of the same book, the first published in 1960, the second in 1962. The style is still naturalistic, but the body is now covered, the three figures all have their back to us, and the dagger - real but symbolic - has become the dominant factor in the design.

But this sort of cover - which so agitated my early teenage hormones when these books, now thoroughly foxed, ended up in that Wimbledon bookshop a few years later - was already doomed: the cooler, thinner, subtler, more graphic style of the early ‘60s soon replaced it. Here are two editions of the same book, the first published in 1960, the second in 1962. The style is still naturalistic, but the body is now covered, the three figures all have their back to us, and the dagger - real but symbolic - has become the dominant factor in the design.

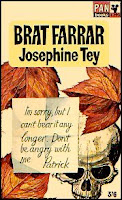

By 1964, people - whether fighting, lusting, screaming or dying - had started to disappear altogether. The history of post-war paperback book covers deserves an exhaustive, heavily illustrated, large-format hardcover work all to itself. Meanwhile, the web abounds with excellent sites for those of us who just like to feast our eyes on them. The most relevant to this article is the the World of Pan Collectorswebsite. American covers are well represented at the Vintage Paperbacks site. Hank Janson covers can be found at Fantastic Fiction. And here’s a collection of books about cover designs available at Amazon.

By 1964, people - whether fighting, lusting, screaming or dying - had started to disappear altogether. The history of post-war paperback book covers deserves an exhaustive, heavily illustrated, large-format hardcover work all to itself. Meanwhile, the web abounds with excellent sites for those of us who just like to feast our eyes on them. The most relevant to this article is the the World of Pan Collectorswebsite. American covers are well represented at the Vintage Paperbacks site. Hank Janson covers can be found at Fantastic Fiction. And here’s a collection of books about cover designs available at Amazon.

No comments:

Post a Comment